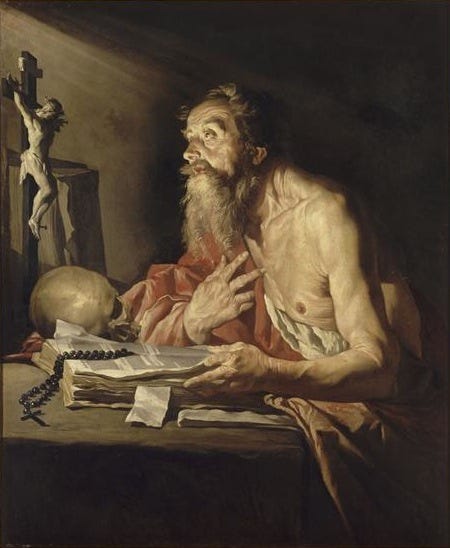

Historical Sketch: Jerome's Temper

If Jerome can be a saint, there's hope for us all!

Photo by Matthias Stom - Oeuvre du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, Public Domain.

When you consider the nasty personal insults Jerome wrote during his long years of scholarship, the friends he managed…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to My Secret is Mine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.