by Sandra Miesel

Fortunatus and Radegund met in what had been Roman Gaul and was in that day the Kingdom of the Franks. The Frankish invaders had been nominally Catholic since the baptism of their king, Clovis, in 496. But Christianity had little impact on the behavior of Clovis and his descendants, the feud-prone, polygamous and bloodthirsty Merovingian dynasty.

Radegund, a Thuringian princess, was born into a troubled family around 520. After murdering her father for the throne, Radegund’s uncle took the young girl and her brother into his household. But the uncle was attacked and killed by the Franks in 531 in revenge for slaughtering Frankish hostages.

Although Radegund was still a child, she enthralled the victorious Frankish king, Clothar. He cast lots with his brother and won her as part of his booty. Clothar sent Radegund to a royal manor to grow up so he could make her his queen.

Radegund became a Catholic, and was given a good education based on the Church Fathers. Although she tried to escape, she was married to Clothar in 540, fifth of perhaps seven wives, some of whom were still living. But, for the duration of the marriage, Radegund was the principal queen.

Radegund gamely fulfilled her state duties, trying to temper her husband’s brutality with generous almsgiving and intercession for royal prisoners. She tended the poor and sick with her own hands, ate humble fare at banquets, and secretly wore a hairshirt under her royal robes during Lent. “More Christ’s partner than her husband’s companion,” (as Fortunatus would later write) she would slip out of Clothar’s bed whenever possible to pray, much to the king’s irritation.

After a decade or so of childless marriage, Clothar murdered Radegund’s younger brother while she was away from the palace. The grief-stricken queen fled to Saint Medard, the bishop of Noyon, and demanded to be made a nun. Manhandled by royal supporters, the bishop hesitated. Frankish law forbade a woman to take religious vows without her husband’s permission. When Radegund clothed herself in monastic garb anyway, the bishop yielded.

Radegund retired to a royal manor that Clothar had given her. Consumed by zeal for doing good, she gave away her royal regalia and threw herself into the service of the needy even more vigorously than before. After awhile, Clothar wanted his wife back. He may have planned to recapture her by force.

After some confusing maneuvers, Clothar and Radegund reached an accommodation negotiated by Saint Germanus, Bishop of Paris. The king released Radegund, endowed a monastery for her at Poitiers, and begged her pardon. Radegund forgave Clothar and may have promised to do penance for his sins in that her mortifications became far more drastic after this point.

Clothar—who would die soon—had much to repent of, including orders to burn a rebellious son alive with his whole family.

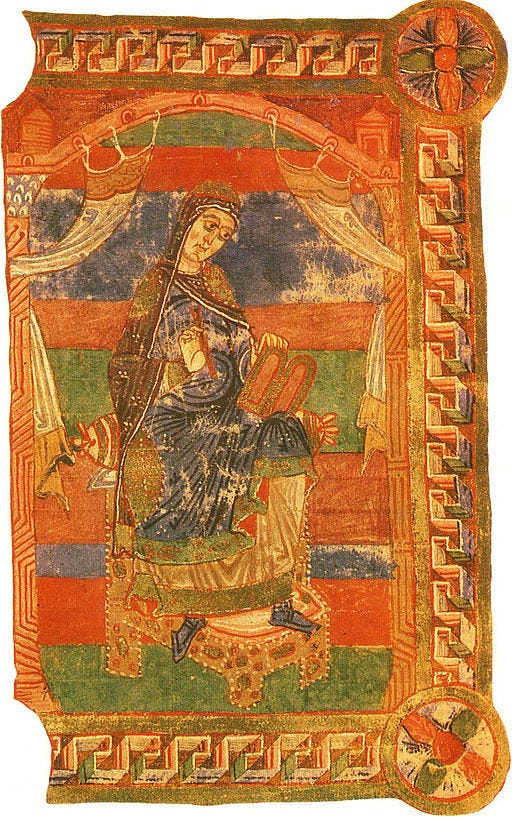

Germanus blessed Radegund’s new monastery of the Virgin Mary and professed her nuns. But the former queen remained canonically a deaconess and declined the post of abbess, giving that office to her foster-daughter, Agnes.

Radegund led the community in the fervor of her vigils, the humility of her service, and the rigor of her austerities. When not reading the scriptures, she had them read to her. She bathed the sick, scrubbed vegetables, cleaned privies and wore sackcloth—“generous to all, but stingy with herself.”

Into this sealed garden of sanctity wandered Venantius Fortunatus, an exquisitely refined Italian with a gift for poetry and fine living. He was born in Trieste in 530 and educated at Ravenna, cities still part of the Eastern Roman Empire. The terrible Gothic Wars ravaging the rest of Italy somehow never touched his life.

Sometime in the 560s, Fortunatus embarked on a very leisurely pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Martin of Tours to thank the saint for healing his eyes. A man excessively eager to please, Fortunatus left a trail of pretty poems wherever he quested.

After reaching Tours, Fortunatus went on to nearby Poitiers and saw Radegund. Even in middle age, she entranced him as she had King Clothar 30 years earlier. “Her influence fell upon him like a consecration,” says medievalist Helen Waddell.

Fortunatus took holy orders, and settled down as the confessor and steward of Radegund’s monastery. He sent Radegund gentle love-poems and bouquets. (See an example here.) He declared that her poems in response “restored honey to the wax tablets they were written on.” More cozily, Radegund urged him to eat more eggs and the abbess Agnes made him cheese with her own hands.

But the level-headed Radegund was too dedicated to her Heavenly Spouse to be take Fortunatus’ attentions as anything but honorable friendship. And life at Poitiers was scarcely the idyll it at first appeared.

War raged around it as Clothar’s sons fought for the kingdom, two of them incited by their feuding wives. Radgeund wrote all parties urging peace and tried to be a mediator. Her impact was temporary at best. But Radegund was determined to protect her ark of refuge and her family in Christ. Besides prayer and penance, she collected relics as supernatural defenses. She sent to Constantinople for a fragment of the true cross, accompanied by a heart-rending letter to her surviving cousin who had fled there years earlier.

Scholars are divided on whether Radegund, Fortunatus or the two in collaboration wrote this poetic letter, but it weeps a lifetime of loneliness. And, by the time it reached Constantinople, Radegund’s cousin was dead.

When the precious relic of the true cross arrived, in 569, Fortunatus wrote the glorious hymn Vexilla regis (“The banners of the king go forth”) which would become the marching son of the Crusades, half a millennium hence. In another burst of inspiration, he added the Pange lingua gloriosi (Sing my tongue the Savior’s triumph).

Radegund’s monastery changed its name to Holy Cross. Twenty years passed before she died peacefully there on August 13, 587. Saint Gregory of Tours celebrated her funeral in place of the hostile local bishop.

Fortunatus wrote a Life of Radegund, emphasizing her mortifications and miracles so that future generations would remember his beloved as a saint. Confident that she would draw him after her into heaven, Fortunatus ended his days in 609 as Bishop of Poitiers.